I had a set of old silverware that was left to me by a cousin of my mother’s whom I’d never met. It had an art deco pattern, and was monogrammed with the letter B. A couple of weeks ago I remembered it, lying in its wooden box in a drawer. I had never used it, even once, and I decided that it was time to let it go, as Cousin Helen? Or Florence? had, more than thirty years ago.

I looked at the back of a teaspoon and tried to decipher the tiny markings. They began with an H with a circle around it, then a W, then what looked like an English pound sign, then a copyright C, the word STERLING, and “PAT. 1917”. I looked it up. The H was for Hirsch & Oppenheimer of Chicago, active from 1904-1922. The design was probably patented in 1917. I couldn’t find out what the W represented.

I checked on the net to see if it had antique or commercial value, and it didn’t seem to; I asked my sister if she wanted it, but she had already inherited two sets of silverware of her own. My friend found the name of a place in Nungambakkam that called itself a silver refinery. We gathered all the knives, forks, spoons, salad forks, soup spoons, and butter knives, and dumped them unceremoniously into a cloth bag.

The street where the refinery was said to be located was too narrow for sidewalks, crowded with one-room shops: Fancy Stores, dry-goods stores where you stand on the street to talk to the shopkeeper, who is separated from you by a counter with large glass jars of plastic-wrapped sweets, and hanging strings of individual sachets of shampoo and paan masala. There was no sign of a refinery. We asked a man perched on a parked motorcycle if he knew where the refinery was, and he nodded and gestured to the building in front of which he was sitting. I guessed that he lived or worked there, and that the motorcycle served as his veranda, a place to sit and get some fresh air. He had a handsome, smiling face, gray hair, and a big belly.

He ushered us into a narrow passageway, dark, but with sunlight at the end of it, shining through an opening in the ceiling. Before we reached the sunlight we turned to enter a small room. There was no furniture except a table in one corner, with a glass-fronted cabinet on top containing an electronic scale. Woven plastic mats covered most of the floor, and framed lithographs of gods hung on the wall, along with a garlanded formal photograph of the founder of the business, wearing a Marathi cap and with a Marathi name, Something Rao Patil, lettered below his formally expressionless face. On one side, embedded in the floor, were two round steel plates, or anvils, with two short-handled mallets behind them.

My friend and I sat down on the mats, but the man from the motorcycle gestured for us to move to one side. I hastily sidled over, so that we both occupied only half of the space. Now another man arrived, carrying a plastic chair, and after him came an older man with thin white hair, wearing a white undershirt and veshti. He was clearly the proprietor. He sat on the chair, while we sat on the floor at his feet like supplicants. The motorcycle man and the younger one who had just arrived sat down by the two round plates.

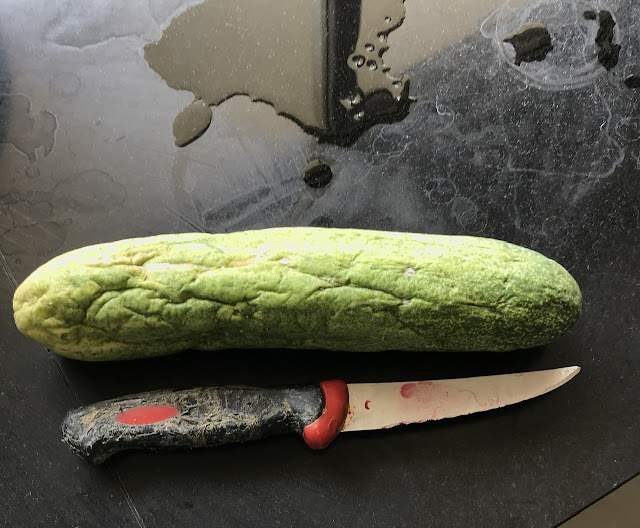

We explained our business and spilled the silverware out on the floor. The two workmen looked it over, held up pieces of it, tried to bend them, put a drop of what the old man said was nitric acid on the back of one of the spoons. The old man watched, and mumbled some directions that I couldn’t understand. They put everything into a wok-shaped pan, except for the knives. Their blades were stainless steel, which they separated from the handles by hammering them on the anvils, one for each of them. The knife handles were hollow, and were filled with reddish dirt, so that they would keep their shape. When the workers emptied out the dirt from each handle, I felt a sense of wonder: more than a hundred years since this dirt had been closed up inside! Then I realised: what is a hundred years to dirt, after all?

So they hammered and bent and flattened, and finally brought out a small crucible, a little bigger than a coffee mug. They filled it with silver pieces, and carried it and the pan containing the rest of it into an adjoining room. This had been nothing but a dark doorway to me, but I stood up and peered in, and saw a fireplace there, raised to about waist height. They placed the crucible and lit the gas so that flames roared up around it, and began to feed bits of silver into it, as the molten metal reduced in volume.

I returned to the first room and sat down, and before very long it was done, and one of the men brought in a silver bar and placed it in my hands.

It was weighed, and we paid the melting fee – Rs. 300 per kilo of silver bar. My friend put it into her purse, the old man told us that they melted gold as well as silver, we thanked them and walked back through the dark passage to the crowded street, the sunshine, the Fancy Stores, as though there were no refinery here, where people hammered silver and melted it, and gold, too! into cool, heavy bars.